According to a research published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, minors who used cannabis were no more likely than adults to have higher levels of subclinical depression or anxiety, nor were they more susceptible to the links with psychotic-like symptoms.

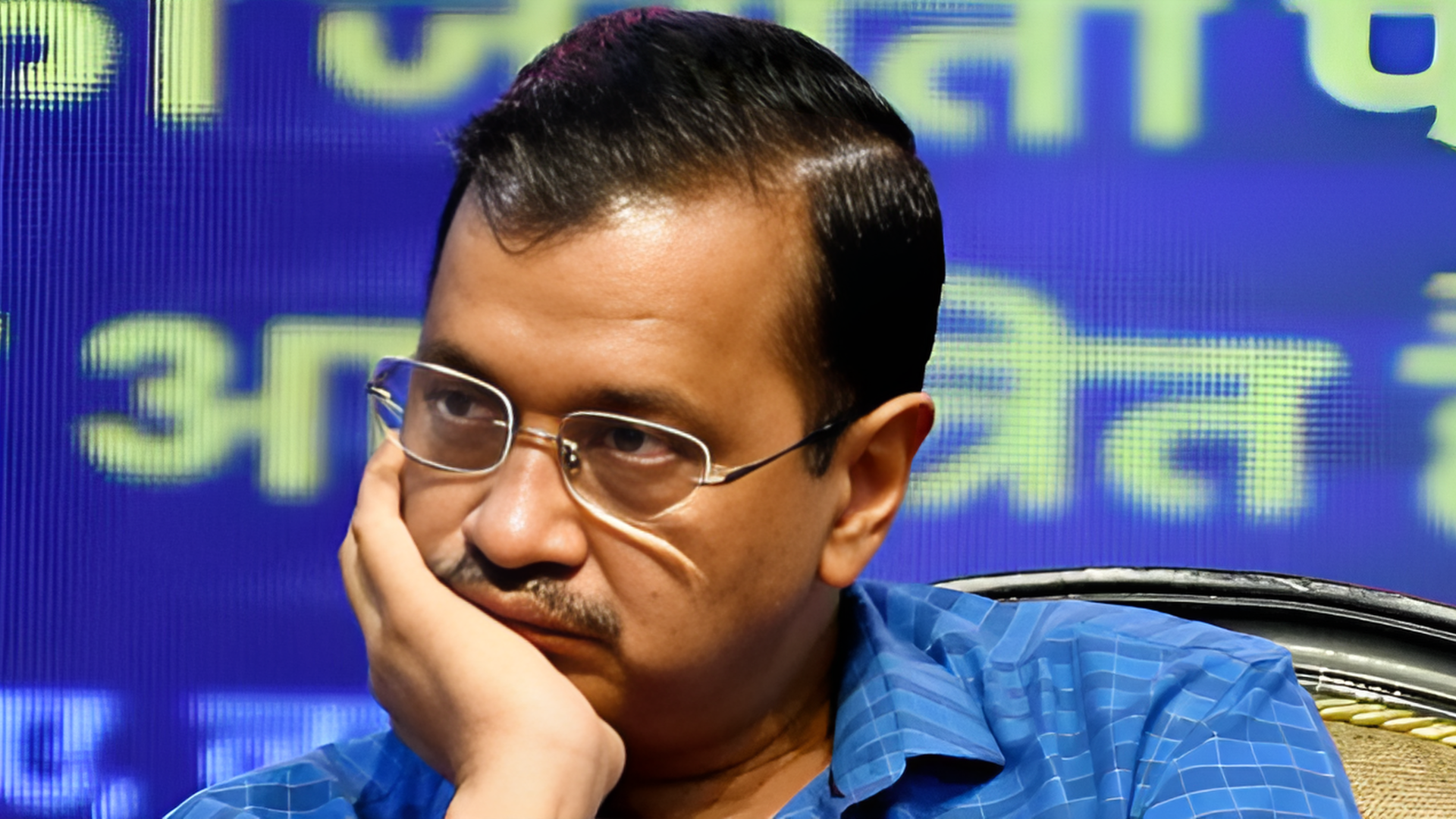

According to a recent study led by UCL and King’s College London researchers, adolescents are more than three times more likely than adults to develop a cannabis addiction, although they may not be at increased risk of other mental health disorders related with the substance.

Lead author Dr Will Lawn (UCL Clinical Psychopharmacology Unit and Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London) said: “There is a lot of concern about how the developing teenage brain might be more vulnerable to the long-term effects of cannabis, but we did not find evidence to support this general claim.

“Cannabis addiction is a real issue that teenagers should be aware of, as they appear to be much more vulnerable to it than adults.

“On the other hand, the impact that cannabis use has during adolescence on cognitive performance or on depression and anxiety may be weaker than hypothesised.

“But we also replicated previous work that if someone becomes addicted to cannabis, that may increase the severity of subclinical mental health symptoms. Given adolescents are also at a greater risk of experiencing difficulties with mental health than adults, they should be proactively discouraged from regular cannabis use.”

The study involved 274 participants, including 76 adolescents (aged 16 and 17) who used cannabis one to seven days per week, alongside similar numbers of adult (aged 26-29) users, and teenage and adult control (comparison) participants, who all answered questions about their cannabis use over the last 12 weeks and responded to questionnaires commonly used to assess symptoms of mental ill health. The cannabis users in the study, on average, used it four times per week. The adolescent and adult users were also carefully matched on gender, ethnicity, and type and strength of cannabis.

The researchers found that adolescent cannabis users were three and a half times as likely to develop severe ‘cannabis use disorder’ (addiction) than adult users, a finding which is in line with previous evidence using different study designs. Cannabis use disorder is defined by symptoms such as, among others: cravings; cannabis use contributing to failures in school or work; heightened tolerance; withdrawal; interpersonal problems caused by or exacerbated by cannabis use; or intending to cut back without success. The researchers found that 50% of the teenage cannabis users studied have six or more cannabis use disorder symptoms, qualifying as severe cannabis use disorder.

Among people of any age, previous studies have found that roughly 9-22% of people who try the drug develop cannabis use disorder, and that risk is higher for people who tried it at a younger age. The increased risk of cannabis addiction during adolescence has now been robustly replicated.

The researchers say that adolescents might be more vulnerable to cannabis addiction because of factors such as increased disruption to relationships with parents and teachers, a hyper-plastic (malleable) brain and developing endocannabinoid system (the part of the nervous system that THC in cannabis acts upon), and an evolving sense of identity and shifting social life.

Adolescent users were more likely than adult users or adolescent non-users to develop psychotic-like symptoms, but the analysis revealed that this is because all adolescents, and all cannabis users, are more likely to newly develop psychotic-like symptoms, rather than cannabis affecting the teenagers differently to adults.

In other words, there was no adolescent vulnerability, as the increased risk of psychotic-like symptoms was an additive effect (of the two already known risk factors for psychotic-like symptoms, cannabis use and adolescent age), rather than an interaction between age and cannabis use. The researchers say this fits in with prior evidence that cannabis use may increase the likelihood of developing a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia, but they warn their study did not investigate the risk of clinical psychosis or schizophrenia.

The researchers found that neither teenage nor adult cannabis users were more likely to develop depressive or anxiety symptoms than non-users. Only the adolescents that have severe cannabis use disorder had worse mental health symptoms, but the researchers caution that the small sample size for this group limits their confidence in this finding.

The separate study published in Psychopharmacology found that cannabis users were no more likely to have impaired working memory or impulsivity. Cannabis users were more likely to have poor verbal memory (remembering things said to you); this effect was the same in adults and teenagers, so again there was no adolescent vulnerability. However, the researchers caution that cannabis use could impact school performance during a key developmental stage of life.

The researchers caution that these findings were cross-sectional (only looking at one time point), and that longitudinal analyses of how their participants changed over time are ongoing.