In a modest house on the Tunisian island of Djerba, Said al-Barouni has undertaken a mission to preserve the lesser-known heritage of his Muslim community. Utilizing technology and AI, he aims to save ancient religious manuscripts.

The 74-year-old librarian, a member of the Islamic sect Ibadism, took charge of his family’s six-generation library in the 1960s. Since then, he has been racing against time to safeguard any Ibadi manuscripts he can find.

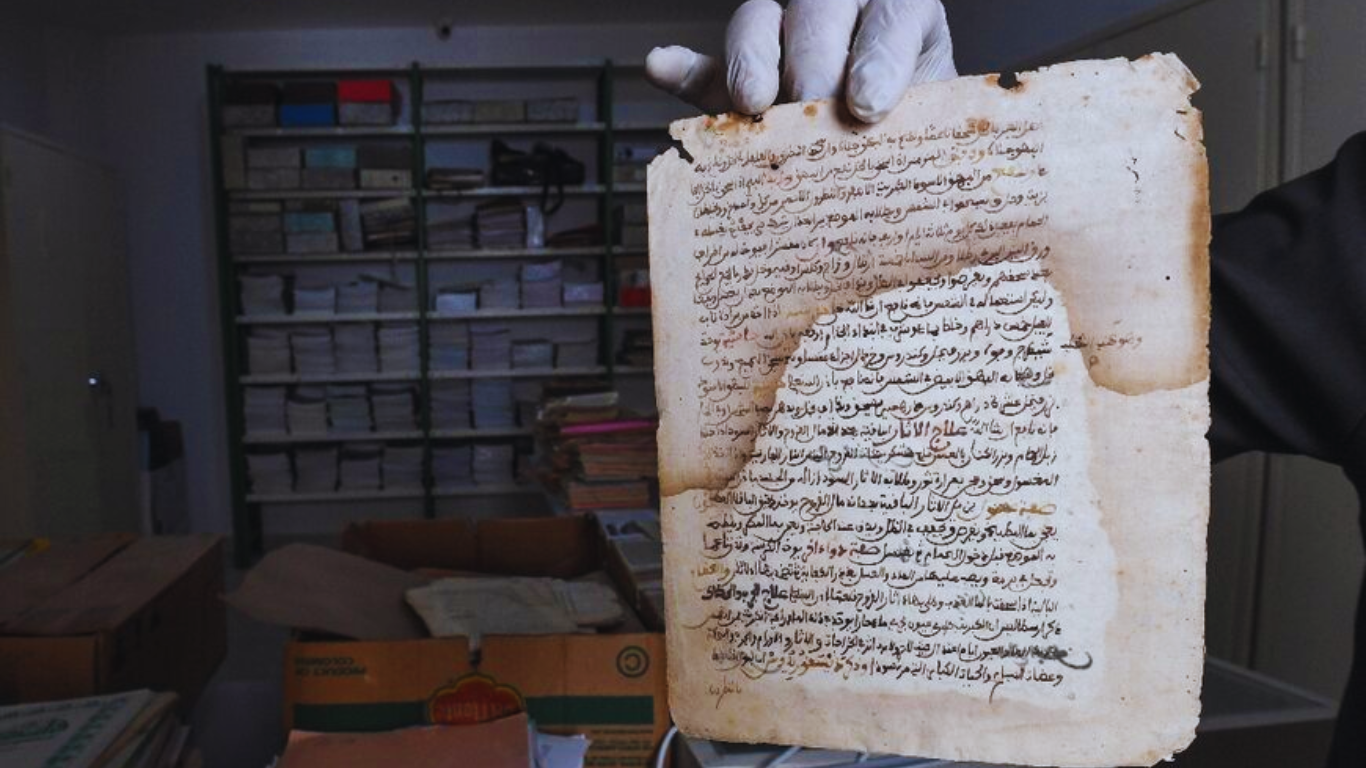

“Look at what Djerba’s humidity has done to this one,” he remarked, holding a deteriorated piece of paper in a climate-controlled room.

Currently, the library houses over 1,600 ancient Ibadi texts on various subjects, including astrology and medicine, dating back to as early as 1357.

ALSO READ: Joe Biden Brings In Restrictions On Asylum Seekers Over Immigration Concerns

However, Barouni continues to seek more literature, which has been dispersed among families over centuries as they practiced their faith in secrecy.

After a disagreement over the succession following the death of Prophet Muhammad in 632 AD, Ibadis were labeled as Kharijites, a divergent Islamic sect considered heretical. They fled to remote regions, primarily in modern-day Oman, where most Ibadis reside today, as well as Libya, Tunisia, and Algeria.

In North Africa, they established a capital in Tihert, present-day Tiaret in Algeria. Their peace was disrupted in the 10th century when the Shiite Fatimid dynasty forced the Ibadis out of their urban centers.

To survive, Ibadis took refuge in Djerba, the Algerian desert, and the remote Nafusa mountains in Libya, as explained by Zohair Tighlet, an expert on Ibadism. They chose to embrace invisibility to preserve their existence and foster a cultural revival.

Most Ibadi manuscripts are now held in family libraries. “All families in Djerba have libraries, but many manuscripts were sold or traded,” Barouni noted.

In a small conservation room, aged books are stored amid the hum of ozone generators, which prevent harmful organisms like mold from damaging the paper. The manuscripts are dusted and digitized, which Barouni believes is the only viable way to preserve them.

Recognizing the difficulty of reading old Arabic cursive, Barouni has adopted Zinki, an AI software that simplifies ancient texts. Feras Ben Abid, the London-based Tunisian engineer behind Zinki, sees it as a tool to unlock manuscripts inaccessible to most readers and correct misconceptions about Ibadi heritage.

Historically, Ibadism has faced persecution from both Sunni and Shia rulers for its belief that any Muslim, regardless of lineage, can lead after the prophet’s death. “They call us Kharijites, as if we were against the religion,” said Al-Barouni. “But no, we were against tyrants.”

Ibadis, often described as the “democrats of Islam,” have a tradition of a council of elders managing social and political matters to protect their community. This system ended under French colonial rule in Tunisia.

In contemporary Tunisia, Ibadis found safety in Djerba, a haven for minorities recently added to the UNESCO World Heritage list for its unique settlement. The island also hosts a Catholic Christian group and one of the largest Jewish communities in the region, making up a significant portion of its population.

Ibadis brought a unique urban planning approach to Djerba, contributing to its cultural tapestry. Their modest lifestyle is reflected in their architecture, with simple, white-washed mosques, small minarets, and discreet designs.