The Doklam plateau is a small patch of high ground at the tri-junction of India, Bhutan and China. To the untrained eye it is unremarkable—windswept ridges and grassy slopes overlooked by snow peaks. To strategists, it is a knife-edge. Just south of it lies the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow stretch of Indian territory barely twenty-five kilometres wide that connects the rest of the country to the Northeast. Control of Doklam would allow China to overlook this vulnerable lifeline. It is why Bhutan has resisted Beijing’s claims for decades, and why India—by treaty and by necessity—cannot afford to let the balance change.

In June 2017, China tried to do just that. A road-construction team of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began extending a track southward into territory disputed with Bhutan. By 18 June, Indian troops had crossed into the plateau and physically stopped the PLA from moving further and continuing their activity. The stage was set for a confrontation that would last seventy-three tense days. Incidentally, I was Brigade Commander at Dokala in 2008 and Battalion Commander in 2001; having seen the ground and the stakes up close, I knew well why India could not afford to blink.

The standoff began with about 270 Indian troops blocking the Chinese crews at Doka La. Behind them, both sides reinforced quietly. Soldiers stood metres apart, separated by little more than flags and tempers. Chinese state media issued daily threats, warning India of the “lessons of 1962.” Yet the Indian government did not budge. It maintained that China’s attempt to alter the status quo violated understandings between the two sides and infringed upon Bhutan’s sovereignty. On the ridge, the resolve of Indian soldiers was evident. In monsoon rain and mountain fog, they held their ground without flinching. For the Modi government, this was a calculated stand. To withdraw unilaterally would have ceded not only a patch of ground but the credibility of India’s security guarantees. By confronting the PLA, India signalled that unilateral changes to the boundary would not be tolerated, even at the risk of escalation.

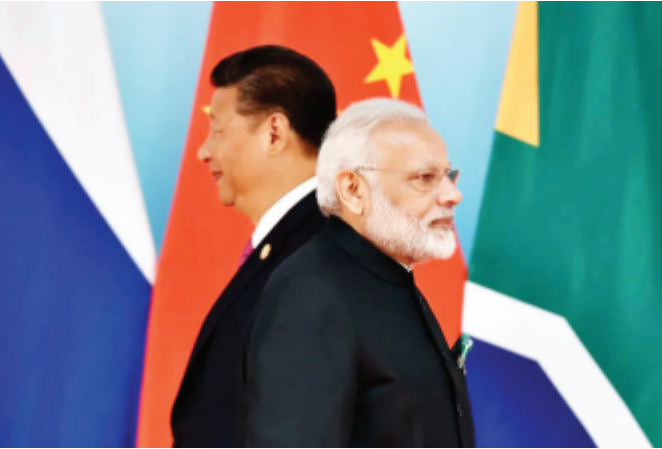

While soldiers stood firm, diplomacy worked in the background. National Security Adviser Ajit Doval travelled to Beijing, and foreign-ministry officials kept up a steady dialogue. Prime Minister Modi met President Xi Jinping informally at the BRICS summit in Xiamen. The tone was markedly different from the shrillness of China’s official statements. India’s approach was calm, almost understated, reinforcing that it sought disengagement rather than confrontation. This combination of resolve and restraint created space for compromise. On 28 August 2017, the Ministry of External Affairs in New Delhi announced an “expeditious disengagement.” Troops from both sides stepped back from the face-off site. China halted its road work. The status quo ante of June was restored. Each side saved face. For India, the outcome meant that the plateau had not been ceded and the Siliguri Corridor remained secure.

The Doklam standoff carried lessons far beyond the narrow ridge where it unfolded. It showed that China’s pattern of “salami slicing”—pushing small, incremental changes on the ground—could be checked if confronted early and firmly. It proved that Beijing, despite its bluster, was not immune to deterrence when faced with determined opposition. Analysts observed that China “pushes until it hits steel.” At Doklam, it hit steel. The crisis also demonstrated the value of restraint. India did not grandstand or expand the confrontation to other sectors. It kept rhetoric low and avoided humiliating China in public, giving Beijing room to step back without appearing defeated. This approach preserved stability while securing India’s interests. Just as importantly, it reinforced India’s credibility with Bhutan, showing that its treaty obligations were not symbolic. For those of us who had commanded troops in Dokala in earlier years, the firmness of 2017 vindicated a long-held assessment: strength, shown early and clearly, is the surest deterrent.

When China mounted multiple incursions across the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh in 2020, the memory of Doklam loomed large. India again stood firm, rushing troops to forward positions and occupying strategic heights to gain leverage. The clash at Galwan in June 2020 was far bloodier, but India did not blink. Analysts linked the firmness of India’s Ladakh posture to the lessons of Doklam: respond early, hold ground, combine military strength with diplomatic engagement and leave space for disengagement through negotiation. Domestically, Doklam also spurred a push for border infrastructure. Roads to forward posts, bridges across rivers and tunnels through high passes were given fresh urgency, in recognition that deterrence depends not only on courage at the frontline but also on the ability to sustain large deployments in difficult terrain.

Doklam’s effects extended beyond the Himalayas. The standoff underscored the need for India to build coalitions. In the years that followed, the Quad was revived with a sharper maritime focus; Indo-Pacific cooperation deepened with Japan, Australia and the United States; and partnerships with France and other regional powers acquired new momentum. The implicit message was that India would not face China alone, whether on land or at sea. At home, the episode fostered rare political unity. Opposition parties, briefed on developments, chose not to exploit the crisis for point-scoring. This bipartisan approach strengthened the government’s hand in negotiations and signalled to China that India was united across the political spectrum on matters of sovereignty.

The Doklam standoff of 2017 was more than a border incident. It was a demonstration of India’s capacity to blend courage with composure, steel with restraint. By standing firm on the ridge, Indian soldiers prevented a unilateral change that would have imperilled the Siliguri Corridor. By keeping rhetoric measured, the government allowed space for a diplomatic resolution. The outcome restored the status quo, preserved Bhutan’s interests and underlined India’s red lines to China. In the years since, Doklam has become a reference point. It shaped India’s posture in Ladakh, accelerated infrastructure and deepened partnerships. It remains a reminder that territorial integrity is defended not only by geography and treaties but by the resolve to act when tested. Under Prime Minister Modi, that resolve was made plain on a windswept plateau where India drew the line—and held it.

Maj Gen R. P. S. Bhadauria (Retd) is the Additional Director General of the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, and was formerly the Director of the Centre for Strategic Studies & Simulation (CS3) at USI of India. He served in the Indian Army for 36 years.

Novak Djokovic vs Carlos Alcaraz: The Final Between Novak Djokovic vs Carlos Alcaraz is of…

Budget 2026 raises hopes among salaried taxpayers, but government employees should temper expectations, as no…

HBO’s Harry Potter series will premiere in early 2027, adapting J.K. Rowling’s universe over ten…