By all indications, the upcoming assembly election in Uttar Pradesh is likely to be a bipolar contest between the Samajwadi Party-led alliance and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The two main players are busy stitching or protecting their caste coalitions as we approach the first phase of the election.

The bipolarity of this election is a first for the most populous state of the country in recent memory, which by virtue of the weakening or disintegration of political formations, like the Congress and the socialist parties.

The inability of the Congress to gather itself in the state despite repeated attempts and momentary success in the 2009 Lok Sabha election and the inexplicable underplay by the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has impacted the political diversity of the state.

The BJP’s ability to attract different caste groups under its fold is a well-established fact, which reflects in its momentous victories of the 2017 assembly and 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections. However, so far the Samajwadi Party has not proven itself in being a canopy political formation despite the long innings in politics of its founder Mulayam Singh Yadav.

It is a well-known fact that when the Janata Dal disintegrated, Mulayam Singh sought refuge in caste kinship among Yadavs to create a niche for himself, just as a fellow Yadav, Lalu Prasad, was doing it in the neighbouring Bihar.

With the caste coalition of the Janata experiment broken, the Samajwadi Party managed to survive well in a state of political diversity despite religious polarisation favouring the rival BJP every now and then. Suddenly, it is faced with the bipolarity of 2022, which has thrown challenges its leadership has never faced earlier. To cross the halfway mark in the assembly, the party is facing the difficult task of forcing its way out of the comfort zone of Yadav politics, or for that matter, even beyond the OBC space as well.

Its past performance in assembly elections tells a story of the limitation of single-caste politics in north India. The maximum vote share it has ever got was about 29 per cent in the 2012 assembly election when it formed the government in the state, defeating the incumbent BSP government. Barring this election, the vote share of the Samajwadi Party has averaged around 23 per cent. It won a comfortable victory in 2012 with 29 per cent of vote share because the election was multi-cornered with even the Congress registering a double-digit vote share after decades. This was also the time when the BJP was at its lowest post-Hindutva 1.0, which could roughly be defined as the period between 1991 and 1996 that saw a surge in religious polarisation in north India.

In the phase of Hindutva 2.0, the period starting 2014 since the rise of Narendra Modi in the party, the BJP has reinvented itself and the idea of majoritarianism with aggression and precision of the textbook of political theory. The most impactful chapter of this textbook is Uttar Pradesh where it is holding on to the largest vote share it ever got since 2014. It bagged 42 per cent votes in the 2014 Lok Sabha election, 40 per cent in the 2017 assembly election and progressed further and almost touched the 50 per cent mark in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. It is evident that if this trend holds, then no other party stands a chance against the BJP irrespective of the social coalition they try to create.

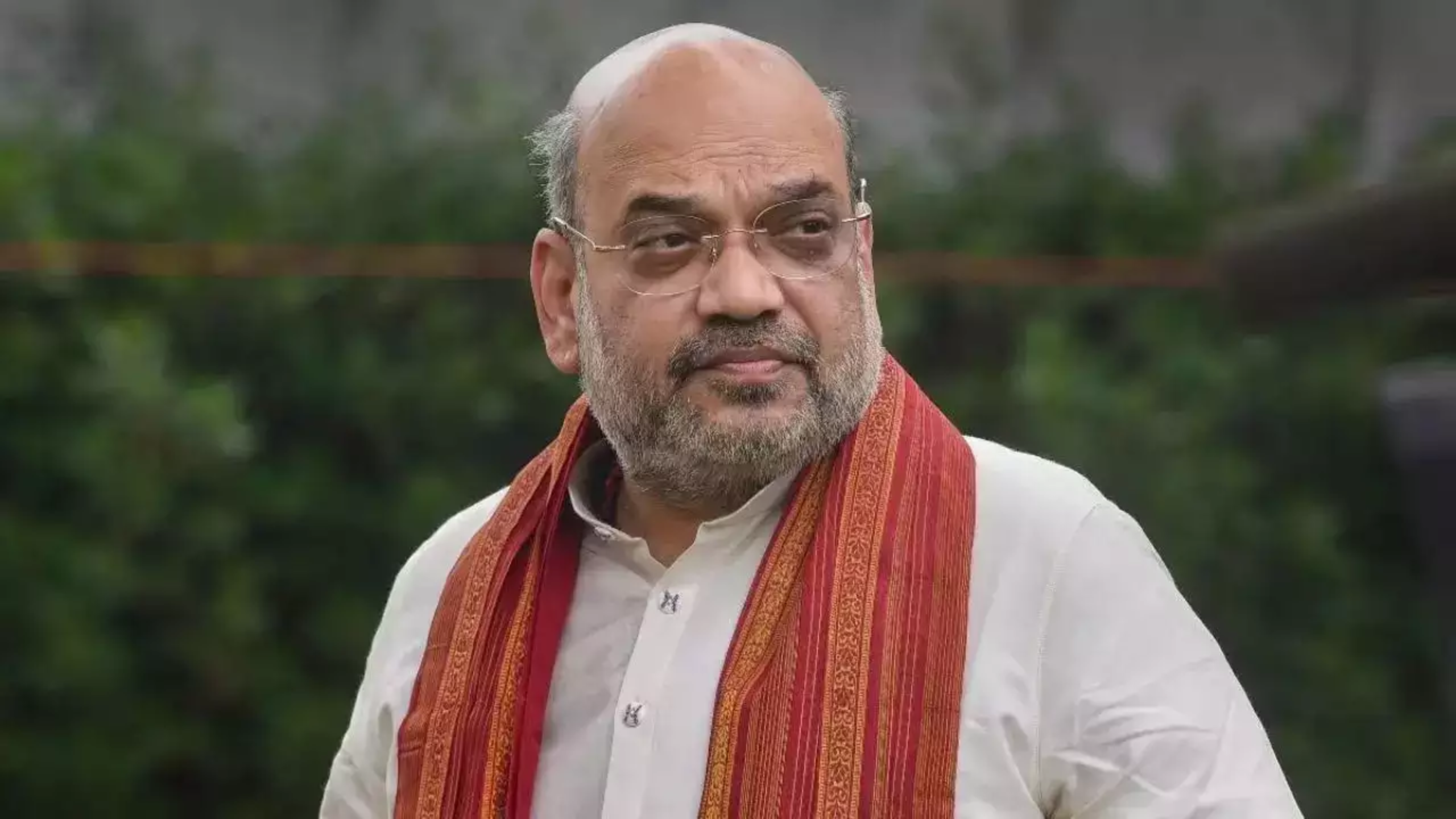

The BJP does not seem to be in a mood to water down the Hindutava rhetoric, as was visible with the recent campaign of home minister Amit Shah in Kairana in the western part of the state and which saw devastating riots before the 2014 Lok Sabha election.

However, after eight years at the Centre and five in the state and a section of the right-wing ecosystem looking at Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath as a challenger to Modi in years to come, the BJP is likely to shed some support in the form of anti-incumbency and factional tension.

A series of instances of political discomfort the BJP has faced through the protests against anti-citizenship and farming laws and mishandling of the pandemic, the Samajwadi Party may be right in thinking that it stands to gain. But, the Samajwadi Party should ponder over how sharp the decline in the BJP’s vote share will be and if the Samajwadi Party can gather enough social groups to upset the BJP equations.

The Samajwadi Party will wish that the BJP drops its vote share to the level of Hindutva 1.0 of 1991-96, when it hovered between 31 and 33 per cent. This seems like a massive drop for the BJP, but it seems a possibility since retaining a 40-plus per cent of vote share in the absence of a clear Hindutva wave may not work.

However, if the BJP settles somewhere between the vote share of Hindutva 1.0 and Hindutva 2.0, the Samajwadi Party may find its canopy too small to hit the halfway mark. It should carefully study the performance of Lalu Prasad’s party in the neighbourhood which has the same social base among the dominant OBCs and Muslims as Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh.

Since the bifurcation of Bihar, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) has been struggling to cross the halfway mark on its own. In the 2020 assembly election, Tejashwi Yadav did not attempt to or could not make any caste coaltions beyond its traditional Yadav-Muslim combine. He did not ally with Upendra Kushwaha’s Rashtriya Lok Samata Party, which could have added the Koeri OBC vote, Jitan Ram Manji’s Hindustani Awam Morcha, which could have brought in the SC Musahar vote, or Mukesh Sahani’s Vikassheel Insaan Party which could have added the OBC Nishad vote to the MY umbrella.

While Tejashwi Yadav hoped that at the height of the Covid pandemic the returning migrant voters will vote on the class lines, but they chose to vote their caste. A poll published by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies forcefully argues that only Yadavs (83 per cent) and Muslims (76 per cent) voted overwhelmingly for the RJD alliance, the only other caste voting more for the RJD alliance than the BJP alliance being the Ravidas with 34 per cent vote share.

In Uttar Pradesh, the Muslim-Yadav voter base constitutes about 25 to 28 per cent of the total voters. To grow beyond this combination and become a challenger to the BJP, the Samajwadi Party has entered into various alliances. This is also because an alliance in a state as big as Uttar Pradesh does not have a pan-state presence.

The Samajwadi Party has entered into an alliance with the Rashtriya Lok Dal, which is predominantly a Jat party and has influence in western Uttar Pradesh. The Samajwadi Party has an alliance with the Mahan Dal, which has presence in Rohilkhand and influence on Kushwaha, Maurya and Shakya OBC communities.

In eastern Uttar Pradesh, the Samajwadi Party has tied up with Om Prakash Rajbhar’s Suheldev Bharatiya Samaj Party, which represents the Rajbhar community, Apna Dal (Kamerawadi), which represents the Kurmi community and Janvadi Socialist Party (JSP), which mainly represents Nonia community within the OBC.

A lot of these groups cannot survive on their own and will always need a bigger party to supplement their caste mobilisation. Till this election, most of them were with the BJP and added under-represented OBC and non-Jatav Dalit groups to its support base. Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party, by giving a prominent space to these parties, is trying to undo the MY limitation imposed on the party by his father. If Akhilesh Yadav’s attempt succeeds, it will stand in stark opposition to Tejashwi Yadav’s OBC politics. So far, the support base of the dominant OBC parties in the two states has run parallel to each other, but Akhilesh’s template could redefine this space if it succeeds in March.