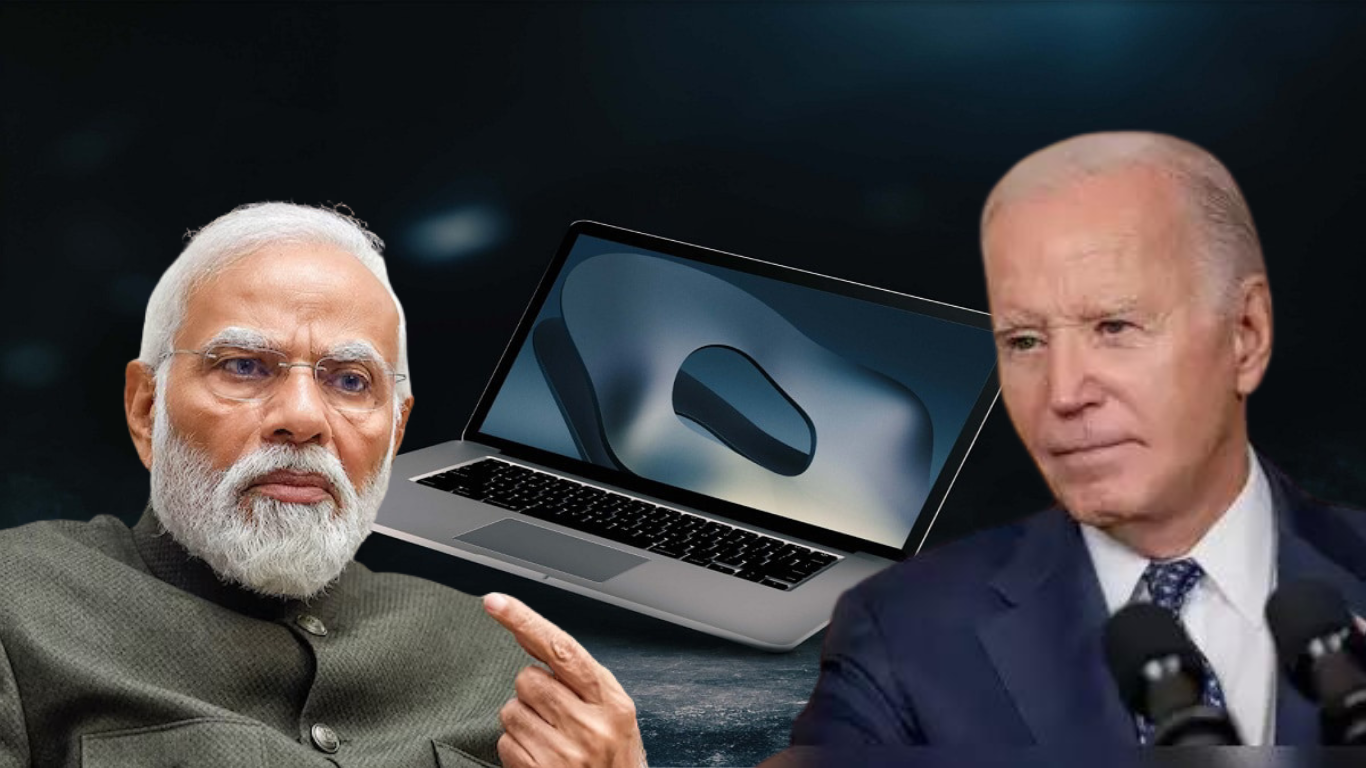

India has reversed its laptop licensing rules after being pressured by US officials.

In August, India introduced regulations mandating companies such as Apple, Dell, and HP to acquire licenses for all imports of laptops, tablets, personal computers, and servers. This move raised concerns about potential sales slowdowns. However, New Delhi quickly reversed the policy within weeks, opting instead to monitor imports and postpone further decisions for a year.

But even after the reversal of laws, the US is still worried about whether India is following its trade commitments and what new rules it might make, according to US trade officials and emails from the government seen by Reuters.

The emails from the U.S. government, obtained through a U.S. open records request, highlight the extent of concern the Indian restrictions raised in Washington. They also show that the U.S. achieved a rare lobbying victory by convincing Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s typically unyielding government to change its policy.

U.S. officials frequently express worries about India’s abrupt policy shifts, which they argue create an unpredictable business climate. India contends that it introduces policies for the benefit of all stakeholders and supports foreign investment, although it often prioritizes local businesses over foreign ones.

Some of the language used in the documents was straightforward, despite the friendly demeanor often portrayed by both sides publicly. U.S. officials were frustrated that India’s alterations to laptop imports came unexpectedly, without prior notice or discussion. They viewed these changes as highly problematic for the business environment and the $500 million worth of annual U.S. exports, as revealed by the documents and emails.

According to research firm Counterpoint, India’s laptop and personal computer market is estimated to be valued at $8 billion annually.

U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai met with Indian Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal in New Delhi on Aug. 26, shortly after the policy was announced. While the USTR’s public statement mentioned that Tai “raised concerns” about the policy and “noted” the necessity for stakeholder consultations, she privately conveyed to Goyal during the meeting that the U.S. urged India to “revoke the requirement,” as indicated by a USTR briefing paper.

India’s unexpected announcement “has led U.S. and other companies to reconsider their business activities in India,” according to the “talking points” outlined in her briefing paper.

During the same period, Travis Coberly, a U.S. trade diplomat in New Delhi, informed his USTR colleagues that Indian officials had acknowledged that the sudden introduction of the laptop licensing policy was a mistake.

“They (India) understand they made a mistake. They admitted it. American companies here have been pressing them on this issue,” he wrote.

Coberly did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi declined to comment on “private diplomatic communications,” redirecting inquiries to the Indian government.

India’s IT ministry did not respond to a request for comment.