The Ladakh Controversy: Why The Union Government Is Stubborn To Grant Ladakh Statehood? ANSWERED In Pics

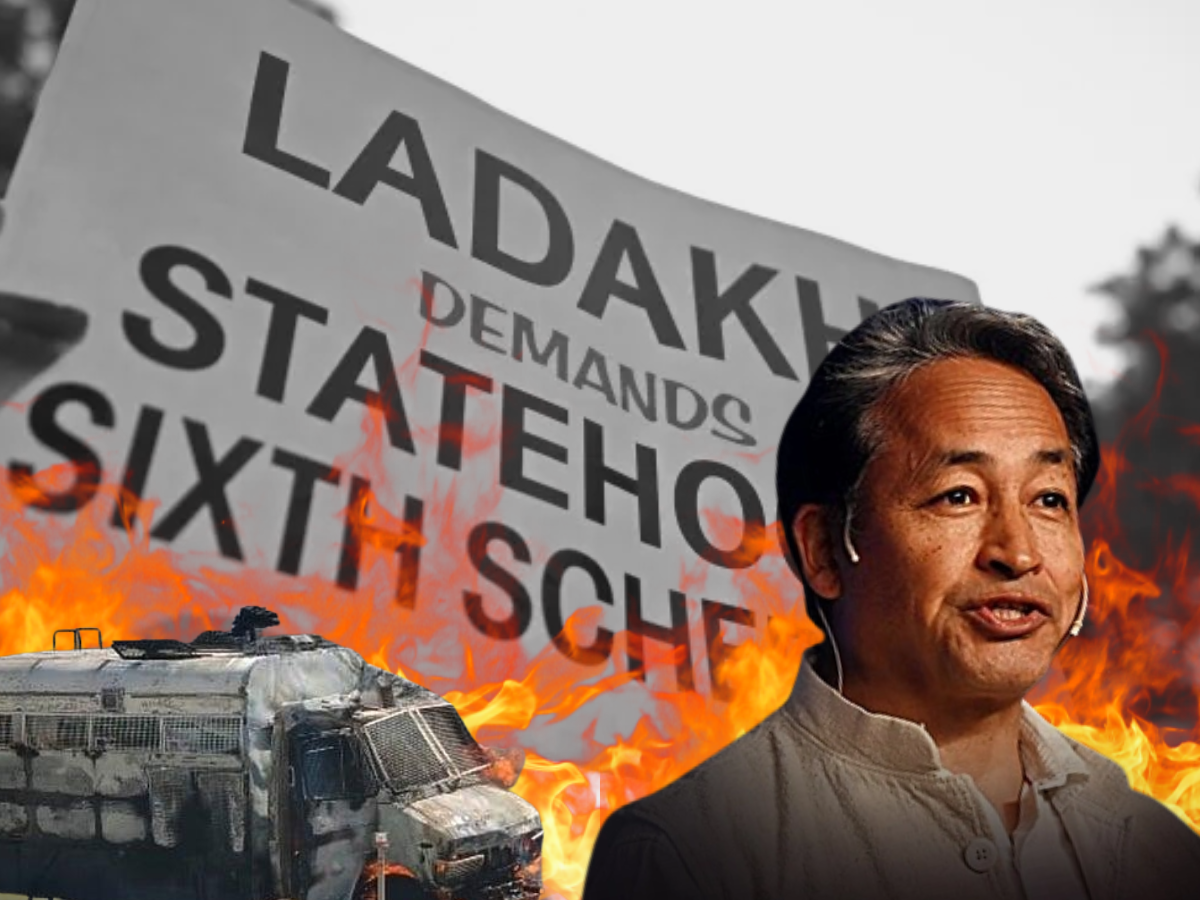

Violent protests erupted in Ladakh recently, leaving four people dead and many others injured. Demonstrators demanding statehood for Ladakh and the extension of the Sixth Schedule targeted a BJP office, setting it on fire. Police responded by firing tear gas shells on September 24, which escalated tensions and triggered a massive shutdown in Leh, organized by the Ladakh Apex Body (LAB). The clashes between protesters and security forces injured over 30 people.

Before the violence, the protests had been ongoing for more than two weeks. Locals have been pushing for statehood and pressing the central government to implement the Sixth Schedule, which grants tribal areas greater administrative autonomy and allows communities to participate in local governance. These demands have roots in a longer struggle, as residents have campaigned for statehood for over three years.

Ladakh became a separate Union Territory in 2019 after the abrogation of Article 370 and the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir. Unlike Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh has no legislative assembly and is administered directly by the central government through a Lieutenant Governor appointed by the President of India. While many initially welcomed the UT status, including social activist Sonam Wangchuk, concerns quickly arose about a political vacuum. Residents felt that the absence of a local assembly limited their ability to govern themselves and safeguard regional interests.

Locals also raised concerns about shrinking job opportunities, weakening land rights, and reduced protections under the Union Territory framework. Frustration over these issues fueled widespread protests and hunger strikes. Notably, for the first time, Buddhist-majority Leh and Muslim-majority Kargil communities united under a single platform, the Apex Body of Leh and the Kargil Democratic Alliance, demanding full statehood for Ladakh. Sonam Wangchuk, known for his activism and social work, has been a prominent supporter of the peaceful protests, urging the youth to voice their demands while promoting dialogue with the central government.

Is There a Solution?

Well, a solution exists, but only in the short term. The concern arises due to Ladakh sharing a border with China. The worry is that if the government agrees to grant statehood, and the ruling party is not the BJP or a trusted ally, it could become difficult for the central government to make border-related decisions or transport arms and ammunition smoothly. There is also a possibility that a newly formed government might provoke forced protests or hire agitators to pressure the Union government. This could escalate tensions and lead to more violence, which is never part of the government’s plan.

Escalating Protests Turn Deadly

Violent demonstrations erupted in Ladakh as locals demanded statehood and implementation of the Sixth Schedule. On September 24, clashes intensified when protesters set fire to a BJP office. Police used tear gas to disperse the crowds, triggering a widespread shutdown in Leh town. Four people lost their lives, and over 30 sustained injuries. The unrest followed more than two weeks of continuous demonstrations by residents seeking increased autonomy and protections under the Sixth Schedule, which allows tribal regions to manage local governance.

Historical Context: Ladakh as a Union Territory

Ladakh became a separate Union Territory in 2019 after the revocation of Article 370 and the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir. Unlike the former state, Ladakh lacks a legislative assembly and is governed directly by a Lieutenant Governor appointed by the President of India. Initially, residents welcomed the UT status, hoping for better administration and infrastructure. However, concerns soon emerged about a perceived political vacuum, with locals feeling excluded from legislative decisions and unable to safeguard their local interests.

Local Discontent and Protests

The absence of an elected assembly has limited Ladakhis’ control over governance, land rights, and job opportunities. Over the past three years, protests, hunger strikes, and large-scale mobilizations have highlighted these grievances. Notably, for the first time, Buddhist-majority Leh and Muslim-majority Kargil communities collaborated through the Leh Apex Body and Kargil Democratic Alliance to collectively demand statehood and the extension of Sixth Schedule protections. This cross-community alliance underscores widespread dissatisfaction with the current UT administration.

Security Concerns and Strategic Considerations

Ladakh’s strategic position along the Line of Actual Control with China and the Line of Control with Pakistan makes it a sensitive security zone. The central government considers Union Territory status crucial for maintaining direct administrative oversight. This structure allows rapid decision-making on military deployments, border infrastructure, and emergency responses, particularly during tense periods such as the 2020 Galwan clash. Granting full statehood could introduce local politics that may complicate central directives in this high-security region.

Geographical and Infrastructural Challenges

Ladakh’s rugged terrain, comprising high-altitude deserts, steep valleys, mountain passes, and extreme weather, poses major challenges for infrastructure development. Projects require specialized machinery, technical expertise, and substantial funding. Agencies like the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) lead critical projects under initiatives like Project Himank and Vijayak, constructing roads, tunnels, and bridges to ensure connectivity, military mobility, and economic development. These projects rely heavily on central oversight, which a state government may struggle to provide effectively.

Administrative and Population Limitations

Ladakh spans approximately 59,000 square kilometers but has a small population of around 290,000. Administering such a vast, sparsely populated territory as a full state would demand significant resources for self-sustaining governance, revenue collection, and infrastructure. Comparisons with other small UTs like Chandigarh or Puducherry highlight the practical difficulties of converting Ladakh into a full-fledged state without overburdening central support.

Government Response and Talks

The Modi government has consistently resisted statehood and full Sixth Schedule protections for Ladakh. A high-powered Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) committee, formed in 2023 and reconstituted in 2024, explored options such as job quotas and additional parliamentary representation but ruled out statehood as unfeasible. Talks, which briefly resumed in May 2025, remain deadlocked ahead of discussions scheduled for October 6, 2025.

Statehood In Ladakh A Question Mark

While statehood appears unlikely in the near term, authorities may consider expanding the powers of the Ladakh Hill Council to provide residents with more control over local governance. This compromise could address some demands while keeping the territory under central administration, balancing security, development, and administrative efficiency.

The Ladakh statehood debate reflects a tension between local aspirations for autonomy and strategic imperatives of national security. Until a viable solution emerges, Ladakh is expected to remain a Union Territory, with limited self-governance but continued central oversight to manage its sensitive borders, challenging geography, and critical infrastructure needs.